Of course, to make a beer that big you need to start with a lot of ingredients. Malt is often doubled, and hops are too. And, in order for the yeast to have a chance to get through all that sugar before succumbing to the stupor-inducing alcohol, I’ve heard it’s best to pitch at least a pint of healthy yeast slurry in a five gallon batch.

Lucky for me, I have a yeast connection. A few months ago I had the good fortune of meeting the Brewmaster of my local brewery, Aloha Beer Company, and when I mentioned my dreams of making a barley wine, he offered to give me as much yeast as I could carry. I ended up walking out of there with two quarts—definitely more than I needed, but that’s the size of the container I’d brought, and he filled it almost to the brim.

It was lively yeast too, coming straight from a twenty barrel vat, raring to get back to work. In the few minutes I stood there chatting with the Brewmaster, the yeast swelled to fill the container. A few minutes more and the sides of my plastic container had begun to bend outward from the pressure.

I hurried to my car, put the yeast on the floor in front of the passenger seat, and turned the AC up full blast. For the whole ride home I was on edge, wincing at every bump in the road, afraid the yeast would go off like a bomb.

In the end I made it home in time, and got the yeast in the fridge without incident. Little did I know, “incident” was just taking a rain check.

Next day’s brew went fine. I started with ten pounds of Maris Otter grain in the mash, boiled the wort for an hour, adding four ounces of hops during that time. And then I took the kettle off the burner, mixed in four pounds of pale malt extract and three pounds of honey, and brought it back to a boil for thirty more minutes. I wound up with about four and a half gallons with an original gravity of 1.095—not as high as I wanted, but still within style guidelines.

Once the wort had cooled, I pitched the yeast. I wasn’t crazy enough to add all of it, so I split the difference and only threw in half. If a pint was good, I reasoned, then a quart would be twice as good.

And here’s where things went wrong. In all of my research about barley wines, I’d somehow failed to take in the importance of a blowoff tube. I figured a six and a half gallon carboy and an airlock would be good enough. Turns out it wasn’t. Not even close.

About two hours after pitching the yeast, my girlfriend and I heard a percussive sound, sort of a mix between a pop and a thud. “What was that?” she asked. I was afraid I knew.

I ran to the door to the basement, where I’d put the beer. It sounded like it was raining in there. I pulled the latches back quickly, and threw the door open.

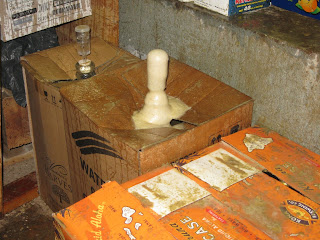

The top of the airlock had blown off, and my carboy had turned into a beer fountain. A mighty stream of liquid shot straight up, to splatter against the ceiling, and then rain down on everything else.

I was able to jerry-rig a blow-off tube pretty quickly—amazing how fast you can make something when you’re supplied with the proper motivation—and I ended up saving about three and a half gallons of the beer. While it’s true I ended up losing almost a quarter of the batch, and several hours time spent cleaning up the mess, I gained something from the experience, too: a name for my barley wine, Kīlauea.

No comments:

Post a Comment